Kiba-dachi survives every modernisation of Karate for the same reason gravity survives fashion: it does not care what we prefer. Every few decades someone decides it is obsolete, impractical, too static for a fast and clever world. And yet it remains—wide, unmoving, still asking the same uncomfortable questions of the body and the mind.

The confusion usually starts with category error. Kiba-dachi is often mistreated as a fighting stance, judged by how poorly it moves, how exposed it looks, how little it resembles what people imagine combat should be. Measured that way, it fails immediately. But Kiba-dachi was never meant to win a fight. It was meant to reveal you. A training stance—deliberately stable, deliberately immobile—it strips away momentum, shortcuts, and clever footwork until only structure remains.

In a world obsessed with speed, Kiba-dachi insists on stillness. In a culture that rewards constant motion, it asks whether you can remain present when nothing exciting is happening. When the legs burn, the knees shake, and the mind begins negotiating for escape, the stance does not change its demand. It waits. This is where its value lives.

Kiba-dachi matters because it teaches what movement depends on but rarely acknowledges: alignment, pressure, breath, patience. It builds the quiet infrastructure beneath technique—the parts no one applauds, but everyone relies on. Long after combinations are forgotten and styles evolve, the stance remains, doing what it has always done: teaching people how to stand honestly under load.

Kiba-dachi is easiest to understand by first clearing away what it isn’t. It is not a frozen snapshot of combat, nor a position meant to be occupied while someone obligingly attacks from the front. It is not a stylistic flourish or a test of how much pain your thighs can endure before your spirit breaks. And it is certainly not a promise that if you stand wide enough and low enough, you will somehow become dangerous by osmosis. None of that was ever the point.

What Kiba-dachi is—quietly, stubbornly—is a training condition. It is a deliberate narrowing of options. The feet are parallel, not because parallel feet are tactically clever, but because they deny rotation and force the hips to behave honestly. The stance is wide, not for intimidation, but to lower the centre of gravity and make balance a matter of structure rather than agility. The knees bend and press outward, not as a pose, but as an ongoing action that reveals weakness immediately if attention drifts.

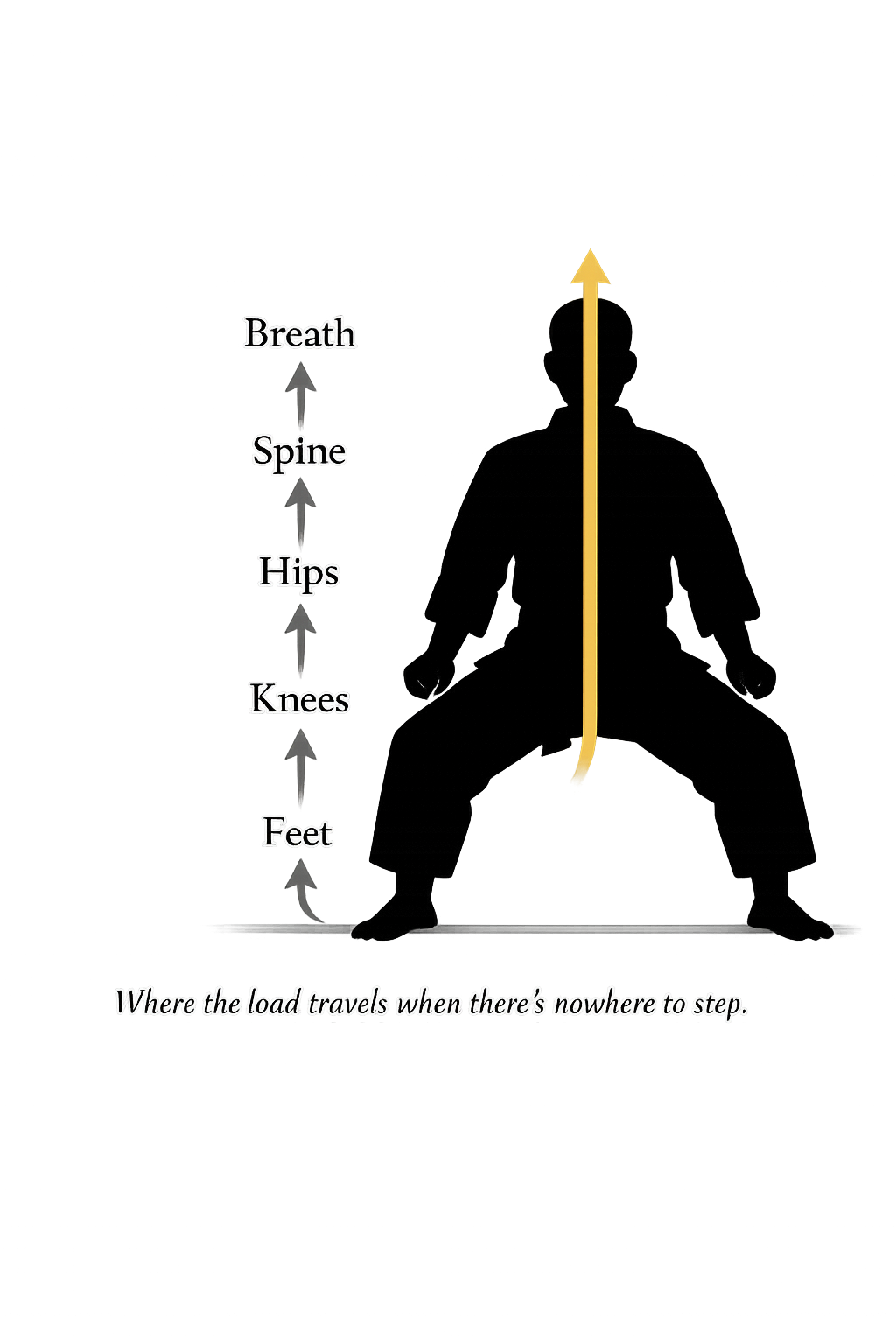

At its core, Kiba-dachi is a lesson in stability under constraint. It teaches how force travels through the body when movement is restricted. It shows whether the spine is stacked or collapsing, whether the hips are engaged or hiding behind tension, whether the breath is working with the body or fighting it. In this way, it functions less as a stance and more as a diagnostic tool.

“Kiba-dachi functions less as a stance and more as a diagnostic tool.”

It does not train movement. It reveals structure.

The trouble begins when Kiba-dachi is misunderstood as an end rather than a means. When taught as a static posture to be endured, it becomes punitive and pointless. When taught as a fighting stance, it becomes embarrassing. But when understood as a way to train alignment, pressure, and calm without the distraction of footwork, it makes sense again. Kiba-dachi is not asking how well you can fight. It is asking whether, when stripped of motion and momentum, you can still hold yourself together.

When motion and momentum are removed, what are you actually relying on?

Stability in Kiba-dachi is not a matter of stubbornness; it is a matter of mechanics. The stance works not because it is wide or low, but because it demands cooperation between parts of the body that would otherwise negotiate separately. When it fails, it does so honestly and immediately, revealing where alignment has been replaced by tension and where intention has gone missing.

Everything begins at the floor

Everything begins at the floor. The feet are planted parallel, distributing pressure evenly from heel to ball, neither clawing nor collapsing. This is not the forward-driving pressure of a fighting stance, but a lateral grounding that asks the legs to support weight without the luxury of stepping. The floor becomes an uncompromising witness. Shift too much into the toes or let the arches cave, and the error is immediately revealed.

The knees are next, and they are rarely innocent. In proper Kiba-dachi they are not simply bent; they press outward in quiet opposition. This outward pressure stabilises the joints and engages the musculature of the thighs and hips in a way that protects rather than punishes. When the knees drift inward, the stance becomes fragile. When they lock, it becomes brittle. Stability lives between those errors, in continuous adjustment rather than frozen effort.

The hips sit heavy but neutral, neither tucked under nor thrust back. This neutrality is deceptive; it requires far more awareness than exaggeration. The hips act as a transmission hub, accepting force from the legs and passing it upward without distortion. Over-tension here blocks that transfer, while collapse turns the stance into a squat masquerading as Karate.

Above the hips, the spine stacks naturally, vertical without rigidity. The chest remains open but uninflated, the shoulders relaxed enough to hang without sagging. This allows force to travel upward cleanly, rather than leaking into tension in the neck or arms. Breath settles low, supporting the structure rather than disrupting it.

In this way, Kiba-dachi teaches stability not as immobility, but as coordinated stillness. Every part is engaged, yet nothing is wasted. The stance holds because the body agrees to hold it together.

The immobility of Kiba-dachi is not a flaw to be apologised for; it is the entire lesson. By removing the option to step, pivot, or retreat, the stance takes away the usual exits that practitioners rely on to mask instability. There is nowhere to go, so whatever is happening in the body must be dealt with exactly where it is happening. This is not cruelty; It is clarity.

“This is not cruelty; it is clarity.”

Movement is forgiving. A poorly aligned body can often escape its own mistakes by stepping away, turning out, or accelerating past the problem. Kiba-dachi offers no such mercy. When the stance is fixed, balance can no longer be borrowed from motion. It must be generated internally, through alignment, breath, and continuous engagement. The body is forced to organise itself, or else quietly unravel.

This constraint has a secondary effect: it reveals how people respond to pressure. As the legs fatigue and the discomfort rises, the mind begins to bargain. The shoulders tighten, the breath climbs into the chest, the knees drift inward. None of this is accidental. It is the nervous system looking for relief. Kiba-dachi does not correct these reactions; it exposes them. In doing so, it becomes a mirror, not just of structure, but of temperament.

The lessons carry beyond the stance itself. The ability to absorb force without retreating underpins close-range striking, clinch work, and throwing. In all of these, stepping away is not always an option. One must remain present, grounded, and functional while pressure is applied. Kiba-dachi rehearses this state in its most distilled form.

By insisting on immobility, the stance teaches a counterintuitive truth: stability is not the absence of strain, but the ability to remain organised within it. When nothing moves, everything matters. This is why Kiba-dachi feels unforgiving. It is not trying to make you comfortable. It is teaching you how not to fall apart when comfort is unavailable.

The Same Stance, Different Questions

Kiba-dachi does not change as a student advances, but the student’s relationship to it does. This is why it can accompany a practitioner from their first class to their last, asking different questions at each stage while never altering its shape. The stance remains simple. The lessons do not.

Awareness before endurance: For the new student, Kiba-dachi is an introduction to the idea that the body must be arranged deliberately. At this stage, the stance is loud and demanding. The legs shake, the feet feel awkward, and the mind struggles to keep track of where everything belongs. The primary lesson is not refinement but awareness. The student learns what “down” feels like, how balance can exist without stepping, and how quickly discomfort arrives when structure is missing. There is also an early lesson in humility. No amount of enthusiasm or rank elsewhere in life exempts anyone from the burn. Kiba-dachi levels the room.

Control without tension: As the student moves into the intermediate stage, the stance becomes less about survival and more about control. The gross errors are mostly gone, but subtler problems emerge. The knees may bend, yet fail to engage outward. The hips may sit low, but hide behind unnecessary tension. Breath often becomes shallow at precisely the moment it is most needed. Here, Kiba-dachi teaches honesty. It reveals how effort is often misdirected, how strength is confused with stiffness, and how the body compensates when attention drifts. The student begins to understand that holding the stance is not enough; it must be held well, repeatedly, without drama.

Efficiency replaces effort: At the advanced level, Kiba-dachi turns quiet again, though it is no less demanding. The stance is now familiar, and that familiarity is its own danger. Advanced students must confront how little effort is actually required when everything is aligned. Excess tension becomes obvious, not because it causes failure, but because it diminishes efficiency. Micro-adjustments take precedence over endurance. The stance becomes a place to study force transmission, to feel how pressure from the floor travels through the legs and hips without distortion. Stability is no longer static; it is alive, constantly maintained through small, almost invisible corrections.

Attention becomes structure: For the black belt, Kiba-dachi ceases to be primarily physical at all. By this point, the legs are capable, the alignment understood. What remains is the mind. The stance now reveals fluctuations in attention, impatience, and emotional state. A distracted mind produces a distracted structure. A calm mind produces a stance that appears almost effortless, even under load. At this level, Kiba-dachi becomes a diagnostic tool, a way to check whether fundamentals are still honoured or merely assumed.

It also becomes a responsibility. A black belt standing in Kiba-dachi teaches whether they intend to or not. Their posture, breath, and composure communicate more than instruction ever could. The stance becomes an expression of lineage, not as tradition performed, but as principles embodied.

Across all ranks, the lesson is the same, though its expression evolves. Kiba-dachi does not exist to be conquered. It exists to be returned to, again and again, as a reminder that learning in Karate does not end with complexity, but deepens through simplicity.

Kata and Kihon: Where Stillness Supports Motion

Within kata and kihon, Kiba-dachi is rarely the destination. It is a moment of consolidation, a place where motion resolves into structure before being released again. When understood this way, its presence in formal practice makes sense. When misunderstood, it becomes one of the most commonly abused elements of performance Karate.

In kata, Kiba-dachi often appears at points of transition—after turns, during directional changes, or beneath techniques that demand stable power generation. Its role is not decorative. It provides a temporary grounding that allows the practitioner to reorganise the body before moving on. The stance absorbs momentum, aligns the hips, and ensures that the next technique is issued from a stable base rather than from leftover motion. When kata performed in Kiba-dachi looks heavy or static, it is usually because this purpose has been forgotten.

Kihon reveals this even more clearly. When basic techniques are practised from Kiba-dachi, footwork is removed from the equation. Power must come from correct sequencing rather than from stepping. A poorly aligned strike becomes obvious when there is no forward movement to disguise it. Conversely, a well-structured technique feels surprisingly strong, even though the body appears stationary. This is one of the quiet lessons of kihon: stability amplifies efficiency when everything else is stripped away.

Common errors arise when practitioners treat Kiba-dachi as something to “hold” rather than something to use. Over-sitting into the stance collapses the hips and dulls transitions. Locking the legs or spine breaks the continuity between techniques. Rushing out of the stance robs it of its function, while lingering in it for theatrical effect turns it into a pose.

Used properly, Kiba-dachi acts as a calibration point inside kata and kihon. It asks whether the practitioner can momentarily settle the body, issue technique cleanly, and then leave the stance without dragging its weight behind them. It is not meant to interrupt flow, but to refine it. In this way, Kiba-dachi supports movement not by moving, but by ensuring that when movement resumes, it does so with integrity.

Teaching Kiba-dachi well requires restraint, which may be its most difficult demand on instructors. The stance is simple, visible, and uncomfortable—three qualities that tempt teachers to overcorrect, overexplain, or overpunish. None of these improve understanding. Most simply teach students how to endure, not how to align.

One of the most common errors in instruction is treating depth as virtue. Forcing students lower than their structure allows may look impressive, but it trades stability for strain and teaches compensation patterns that linger long after the stance is released. Another mistake is duration without intention. Long holds performed mechanically turn Kiba-dachi into a test of tolerance rather than a lesson in organisation. The stance becomes something to survive, not something to study.

Effective teaching shifts the focus away from suffering and toward feedback. Short, intentional holds combined with simple techniques allow students to feel whether the stance is working. Breath becomes a teaching tool rather than a correction shouted from across the floor. When alignment is right, the stance feels heavy but manageable. When it is wrong, it collapses quickly. This contrast teaches more than lectures ever could.

Instructors must also model patience. Kiba-dachi does not reveal its lessons quickly, and students progress through its stages unevenly. Some will struggle physically but grasp structure early. Others will appear strong while relying on tension. Teaching well means seeing past appearances and correcting the root rather than the symptom.

Finally, there is the matter of longevity. Knee health, hip integrity, and spinal alignment must be protected if Kiba-dachi is to remain a lifetime teacher rather than a youthful ordeal. This requires progressive depth, constant attention to outward knee engagement, and permission to adjust based on individual anatomy. Ego has no place here, least of all the instructor’s.

When taught with care, Kiba-dachi becomes an ally rather than an adversary. It stops being a punishment imposed by authority and becomes what it was always meant to be: a quiet, reliable method for teaching students how to organise themselves under load.

Beyond its physical demands, Kiba-dachi works on the practitioner in subtler ways, shaping how pressure is met rather than how technique is performed. When movement is removed and the body is asked to remain present, the mind has little to distract itself with. What emerges is not philosophy in the abstract, but psychology made visible through posture and breath.

In this sense, Kiba-dachi is a practical expression of heijōshin, the ordinary, undisturbed mind. There is nothing dramatic happening in the stance. No attack to respond to, no opponent to read. The challenge lies in maintaining composure while the body works and discomfort accumulates. When the mind chases relief, the structure deteriorates. When attention settles, the stance steadies. The body reflects the mind without commentary.

With deeper practice, Kiba-dachi also gestures toward fudōshin, the immovable spirit. This immovability is often misunderstood as stubbornness or brute resistance. In reality, it is a quality of steadiness. The stance does not resist strain by hardening against it, but by remaining organised within it. This distinction matters. A tense body may look immovable, but it shatters under change. A calm one adapts without losing shape.

Perhaps the most important philosophical lesson Kiba-dachi offers is its indifference. It does not reward effort with praise or punish failure with spectacle. It simply responds. If attention wavers, it shows. If ego intrudes, it becomes heavy. If patience is present, the stance feels almost generous. Over time, this neutrality trains practitioners to seek feedback rather than validation.

“It simply responds.”

In this way, Kiba-dachi becomes more than a stance. It becomes a small, repeatable encounter with reality—one in which the practitioner learns, quietly and without ceremony, how to remain themselves under pressure.

Kiba-dachi offers no final revelation, no moment where the stance is mastered and politely steps aside. Instead, it waits. It waits for the practitioner to return, again and again, bringing a slightly different body, a slightly different mind, and the same old assumptions that will soon be tested. In this way, it resists completion. There is nothing to finish, only something to continue.

What makes Kiba-dachi enduring is not its severity, but its consistency. It asks the same questions every time: Is your structure honest? Is your breath supporting you or betraying you? Are you present, or merely enduring until permission to move is granted? The answers change with experience, but the questions do not. This constancy is what allows the stance to grow with the practitioner rather than be outgrown by them.

In a martial art that can easily become cluttered with accumulation—more techniques, more variations, more explanations—Kiba-dachi remains elegantly minimal. It strips training back to essentials and reminds us that refinement often comes not from adding complexity, but from removing what is unnecessary.

To stand in Kiba-dachi is to agree to this ongoing conversation. There is no ceremony, no declaration of arrival. There is only the floor, the breath, and the quiet work of not falling apart. In that simplicity, learning does not conclude. It deepens.